Text by Michael Lee Hong Hwee

Photo by han / yesterday was great

Artistic duos are interesting on three counts. First, they contest the myth of the individualistic artist, whether in terms of the angst-filled loner like Vincent van Gogh, or the extroverted visionary such as Pablo Picasso. Second, regardless of their personal relationships (lovers, siblings or friends), duos have chosen to subsume their individual artistic identities to produce singular expressions. Third, they have decided that two persons – no more, no less – form the best team for creative collaborations.

Collaborations facilitate exchange, mutual inspiration, sharing of resources and tasks, and the assertion of artistic identity and influence. They may also encourage conformity, parasitism, laziness, inequality and irreconcilable conflicts. For every successful collaboration, there are others that end in a fallout or, worse, the failure to produce anything refreshing. One plus one may be less than two.

How do duos make things work?

In The 2nd Singapore Biennale 2008 are a number of works by duos. The Russian-born, USA-based couple comprising Ilya and Emilia Kabakov presents Manas (Utopian City) (2007), an installation-model of an imaginary city in Northern Tibet. Surrounding this ideal city are eight mountains on the peak of which are each built a structure that can facilitate communication with the cosmos. Their installation suggests the possibility of imagining better alternatives to existing physical conditions. The mind is the most adventurous explorer.

An Art in America interview in 2000 includes a footnote stating that, as a teenager in Russia in the 1970s, Emilia was already in love with Ilya, her paternal cousin, but they only got together when they met again in New York in the 1980s. To Ilya Kabakov, Emilia Kabakov is said to be “the one who makes the exhibitions happen, organises the many details, wheels and deals, and collaborates on artistic ideas.” Credit should be given where it is due.

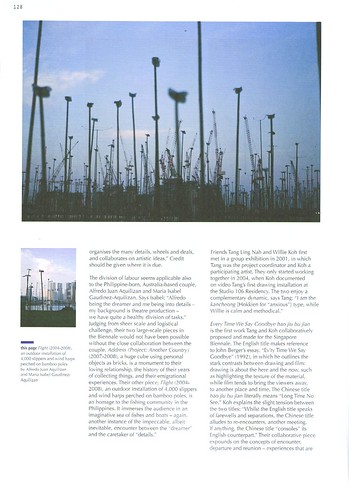

The division of labour seems applicable also to the Philippine-born, Australia-based couple, Alfredo Juan Aquilizan and Maria Isabel Gaudinez-Aquilizan. Says Isabel: “Alfredo being the dreamer and me being into details (my background is theatre production), we have quite a healthy division of task.” Judging from sheer scale and logistical challenge, their two large-scale pieces in the Biennale would not have been possible without the close collaboration between the couple. Address (Project: Another Country) (2007-2008), a huge cube using personal objects as bricks, is a monument to their loving relationship, the history of their years of collecting things and their emigrational experiences. Their other piece, Flight (2004-2008), an outdoor installation of 4000 slippers and wind harps perched on bamboo poles, is a homage to the fishing community in the Philippines; it immerses the audience in an imaginative sea of fishes and boats – again, another instance of the impeccable, albeit inevitable, encounter between the “dreamer” and the caretaker of “details.”

Friends Tang Ling Nah and Willie Koh first met on a group exhibition in 2001, in which Tang was the project coordinator and Koh a participating artist. They only started working together in 2004, when Koh documented on video Tang’s first drawing installation at the Studio 106 Residency. The two enjoy a complementary dynamic, says Tang: “I am the kancheong [Hokkien for ‘anxious’] type, while Willie is calm and methodical.” Every Time We Say Goodbye hao jiu bu jian is the first work Tang and Koh collaboratively proposed and made, for the Singapore Biennale. The English title makes reference to the essay, “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” (1992), in which John Berger outlines the stark contrasts between drawing and film: Drawing is about the here and the now, such as highlighting the texture of the material, while film tends to bring the viewers away, to another place and time. The Chinese title literally means ‘Long Time No See.’ Koh explains the slight tension between the two titles: “Whilst the English title speaks of farewells and separations, the Chinese title alludes to a reencountering, another meeting. If anything, the Chinese title ‘consoles’ its English counterpart.” Their collaborative piece expounds on the concepts of encounter, departure and reunion – experiences that are commonplace but not commonly reflected on. Spanning four spaces (three rooms and an interconnecting open area), the work makes visual references to elements at the site through drawing and video.

With charcoal and paint, Tang has blackened selected areas of the spaces. She does it in two ways: trompe-l'œil (French for ‘trick the eye’), the realistic depiction of three-dimensional spaces onto a two-dimensional surface; and the total or partial blackwashing of physical elements like door frames and light switches. If the first mode creates the optical illusion of environments that one can imaginatively enter, the second mode shatters that illusion by bringing to attention the tactile existence of architectural elements in a given space. The coexistence of these two modes affords a nuanced visual experience. Immersed in the nostalgic or solemn environment, thanks in part to the lack of colour in it, we alternate between looking into the image of a section of an urban space, and awakening to the reality that we are already in such a space. The looking subject self-realises as a looked object.

Koh’s video projections provide oblique illustration and fuels melancholy. The videos’ slow but steady zooms in and out (Koh calls them “breathing”) parody the imaginary journeys through Tang’s illusionist images. Interestingly, these journeys are accompanied by ambient sounds, though these must be from the site or at least partly imaginary, because the video is mute.

Beyond illustration, the images evoke the uncanny through a calculated study of beauty and change. On encountering Koh’s images, one is tempted to hastily name their subject matter. It’s a building. It’s part of a building. It’s in this building. It’s outside. It’s…. This ease of naming is helped by the straight photography of the architectural spaces and structures – clinical and stripped of emotion. Just as one begins to enjoy the upmanship of having identified the subject matter, the image splits, literally, to reveal that they have been manipulated: The symmetrical subject is, in fact, a digital effect. In certain scenes, one does not realise the ‘constructed-ness’ until at an advanced stage, when things appear and disappear drastically along a line of symmetry. Changes to the position, orientation and angle of this invisible line, coupled with the variation in direction and speed of the “breathing,” trigger a series of unease and disappointments.

Symmetry is a cultural marker of beauty, as it approximates the strongest and healthiest in nature. The identity, as well as beauty, of Koh’s moving spaces is alternately accentuated and negated by the illusory symmetry. When the spaces first appear, they assert their existence and beauty by quietly being there. When they start changing shape, due to movement, the plausibility of their existence and beauty is questioned. Witnessing Koh’s metamorphosis of symmetrical architectures is intriguing, depressing and invigorating: The sadness initially in the undercurrents of the innocuous images of spaces comes to the forefront upon the realisation that both their identity and beauty are impermanent, if ever graspable. Yet their physical implausibility does not eradicate an inner logic of possibility. Herein lies the optimism amidst the gloom: If things can change and disappear, might they not also change back and reappear, even or especially if in a different form or context? Departure begets reencounter.

One might gripe the artists’ respective inputs of drawing and video do not meld into a third, new thing. Need they? Perhaps visible integration in this case is not as crucial as the series and layers of emotional experiences on encountering the spaces. Comparisons between the still and moving representations of space, between the physical work and the photographic documentation of it, as well as between the identity or beauty of things in physical and psychological terms, are fruitful ventures in exploring the interplay of space, relationship and memory in our personal contexts.

To further examine this interplay, one might refer to Here, There, Nowhere, a work Tang made for the group show You Are Not A Tourist, in 2007. For this piece, Tang mapped out areas of Singapore’s city centre in a booklet, which contains her charcoal drawings of select urban spaces and Koh’s text contribution of statistical items that require the reader’s input. For example, the charcoal rendition of a part of Citylink tunnels is accompanied by

no. of gutter covers:

no. of kisses:

no. of stolen kisses:

no. of dustbins:

no. of hands, held:

Couched in an objective sense of scientific inquiry, the numerological quiz here belies deep yearnings: to note or recollect exact instances of architectural elements and relational experiences. The apparent lack of emotions in Koh’s texts and videos is strategically deceptive in that it leads the audience to let down their guards, tease them to recall specifics, thereby triggering them to remember intimate moments with loved ones. Sometimes all it takes to break down a tough façade is a simple question. Perhaps likewise, an interesting, though certainly not the only, way to nudge anxiety into (or as) an aesthetic is a ‘calm’ methodology. Finally, in my view, the book work, which pointedly and poignantly addresses Tang’s expressed wish to explore urban dwellers’ relationship with one another and their environment, is an important companion to more profoundly experience their biennale piece.

Photo by han / yesterday was great

Artistic duos are interesting on three counts. First, they contest the myth of the individualistic artist, whether in terms of the angst-filled loner like Vincent van Gogh, or the extroverted visionary such as Pablo Picasso. Second, regardless of their personal relationships (lovers, siblings or friends), duos have chosen to subsume their individual artistic identities to produce singular expressions. Third, they have decided that two persons – no more, no less – form the best team for creative collaborations.

Collaborations facilitate exchange, mutual inspiration, sharing of resources and tasks, and the assertion of artistic identity and influence. They may also encourage conformity, parasitism, laziness, inequality and irreconcilable conflicts. For every successful collaboration, there are others that end in a fallout or, worse, the failure to produce anything refreshing. One plus one may be less than two.

How do duos make things work?

In The 2nd Singapore Biennale 2008 are a number of works by duos. The Russian-born, USA-based couple comprising Ilya and Emilia Kabakov presents Manas (Utopian City) (2007), an installation-model of an imaginary city in Northern Tibet. Surrounding this ideal city are eight mountains on the peak of which are each built a structure that can facilitate communication with the cosmos. Their installation suggests the possibility of imagining better alternatives to existing physical conditions. The mind is the most adventurous explorer.

An Art in America interview in 2000 includes a footnote stating that, as a teenager in Russia in the 1970s, Emilia was already in love with Ilya, her paternal cousin, but they only got together when they met again in New York in the 1980s. To Ilya Kabakov, Emilia Kabakov is said to be “the one who makes the exhibitions happen, organises the many details, wheels and deals, and collaborates on artistic ideas.” Credit should be given where it is due.

The division of labour seems applicable also to the Philippine-born, Australia-based couple, Alfredo Juan Aquilizan and Maria Isabel Gaudinez-Aquilizan. Says Isabel: “Alfredo being the dreamer and me being into details (my background is theatre production), we have quite a healthy division of task.” Judging from sheer scale and logistical challenge, their two large-scale pieces in the Biennale would not have been possible without the close collaboration between the couple. Address (Project: Another Country) (2007-2008), a huge cube using personal objects as bricks, is a monument to their loving relationship, the history of their years of collecting things and their emigrational experiences. Their other piece, Flight (2004-2008), an outdoor installation of 4000 slippers and wind harps perched on bamboo poles, is a homage to the fishing community in the Philippines; it immerses the audience in an imaginative sea of fishes and boats – again, another instance of the impeccable, albeit inevitable, encounter between the “dreamer” and the caretaker of “details.”

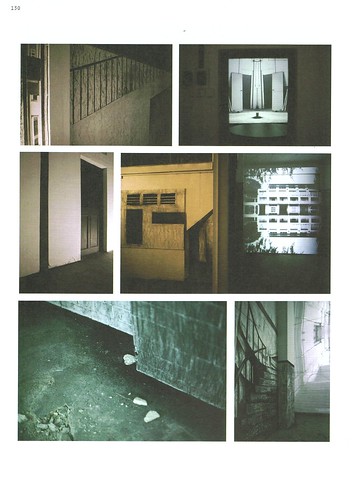

Friends Tang Ling Nah and Willie Koh first met on a group exhibition in 2001, in which Tang was the project coordinator and Koh a participating artist. They only started working together in 2004, when Koh documented on video Tang’s first drawing installation at the Studio 106 Residency. The two enjoy a complementary dynamic, says Tang: “I am the kancheong [Hokkien for ‘anxious’] type, while Willie is calm and methodical.” Every Time We Say Goodbye hao jiu bu jian is the first work Tang and Koh collaboratively proposed and made, for the Singapore Biennale. The English title makes reference to the essay, “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” (1992), in which John Berger outlines the stark contrasts between drawing and film: Drawing is about the here and the now, such as highlighting the texture of the material, while film tends to bring the viewers away, to another place and time. The Chinese title literally means ‘Long Time No See.’ Koh explains the slight tension between the two titles: “Whilst the English title speaks of farewells and separations, the Chinese title alludes to a reencountering, another meeting. If anything, the Chinese title ‘consoles’ its English counterpart.” Their collaborative piece expounds on the concepts of encounter, departure and reunion – experiences that are commonplace but not commonly reflected on. Spanning four spaces (three rooms and an interconnecting open area), the work makes visual references to elements at the site through drawing and video.

With charcoal and paint, Tang has blackened selected areas of the spaces. She does it in two ways: trompe-l'œil (French for ‘trick the eye’), the realistic depiction of three-dimensional spaces onto a two-dimensional surface; and the total or partial blackwashing of physical elements like door frames and light switches. If the first mode creates the optical illusion of environments that one can imaginatively enter, the second mode shatters that illusion by bringing to attention the tactile existence of architectural elements in a given space. The coexistence of these two modes affords a nuanced visual experience. Immersed in the nostalgic or solemn environment, thanks in part to the lack of colour in it, we alternate between looking into the image of a section of an urban space, and awakening to the reality that we are already in such a space. The looking subject self-realises as a looked object.

Koh’s video projections provide oblique illustration and fuels melancholy. The videos’ slow but steady zooms in and out (Koh calls them “breathing”) parody the imaginary journeys through Tang’s illusionist images. Interestingly, these journeys are accompanied by ambient sounds, though these must be from the site or at least partly imaginary, because the video is mute.

Beyond illustration, the images evoke the uncanny through a calculated study of beauty and change. On encountering Koh’s images, one is tempted to hastily name their subject matter. It’s a building. It’s part of a building. It’s in this building. It’s outside. It’s…. This ease of naming is helped by the straight photography of the architectural spaces and structures – clinical and stripped of emotion. Just as one begins to enjoy the upmanship of having identified the subject matter, the image splits, literally, to reveal that they have been manipulated: The symmetrical subject is, in fact, a digital effect. In certain scenes, one does not realise the ‘constructed-ness’ until at an advanced stage, when things appear and disappear drastically along a line of symmetry. Changes to the position, orientation and angle of this invisible line, coupled with the variation in direction and speed of the “breathing,” trigger a series of unease and disappointments.

Symmetry is a cultural marker of beauty, as it approximates the strongest and healthiest in nature. The identity, as well as beauty, of Koh’s moving spaces is alternately accentuated and negated by the illusory symmetry. When the spaces first appear, they assert their existence and beauty by quietly being there. When they start changing shape, due to movement, the plausibility of their existence and beauty is questioned. Witnessing Koh’s metamorphosis of symmetrical architectures is intriguing, depressing and invigorating: The sadness initially in the undercurrents of the innocuous images of spaces comes to the forefront upon the realisation that both their identity and beauty are impermanent, if ever graspable. Yet their physical implausibility does not eradicate an inner logic of possibility. Herein lies the optimism amidst the gloom: If things can change and disappear, might they not also change back and reappear, even or especially if in a different form or context? Departure begets reencounter.

One might gripe the artists’ respective inputs of drawing and video do not meld into a third, new thing. Need they? Perhaps visible integration in this case is not as crucial as the series and layers of emotional experiences on encountering the spaces. Comparisons between the still and moving representations of space, between the physical work and the photographic documentation of it, as well as between the identity or beauty of things in physical and psychological terms, are fruitful ventures in exploring the interplay of space, relationship and memory in our personal contexts.

To further examine this interplay, one might refer to Here, There, Nowhere, a work Tang made for the group show You Are Not A Tourist, in 2007. For this piece, Tang mapped out areas of Singapore’s city centre in a booklet, which contains her charcoal drawings of select urban spaces and Koh’s text contribution of statistical items that require the reader’s input. For example, the charcoal rendition of a part of Citylink tunnels is accompanied by

no. of gutter covers:

no. of kisses:

no. of stolen kisses:

no. of dustbins:

no. of hands, held:

Couched in an objective sense of scientific inquiry, the numerological quiz here belies deep yearnings: to note or recollect exact instances of architectural elements and relational experiences. The apparent lack of emotions in Koh’s texts and videos is strategically deceptive in that it leads the audience to let down their guards, tease them to recall specifics, thereby triggering them to remember intimate moments with loved ones. Sometimes all it takes to break down a tough façade is a simple question. Perhaps likewise, an interesting, though certainly not the only, way to nudge anxiety into (or as) an aesthetic is a ‘calm’ methodology. Finally, in my view, the book work, which pointedly and poignantly addresses Tang’s expressed wish to explore urban dwellers’ relationship with one another and their environment, is an important companion to more profoundly experience their biennale piece.

No comments:

Post a Comment